The Cynical Red Herring of Arming Teachers

By Kristin J. Anderson and Christina Hsu Accomando

February 28, 2018

This article was updated on May 27, 2022

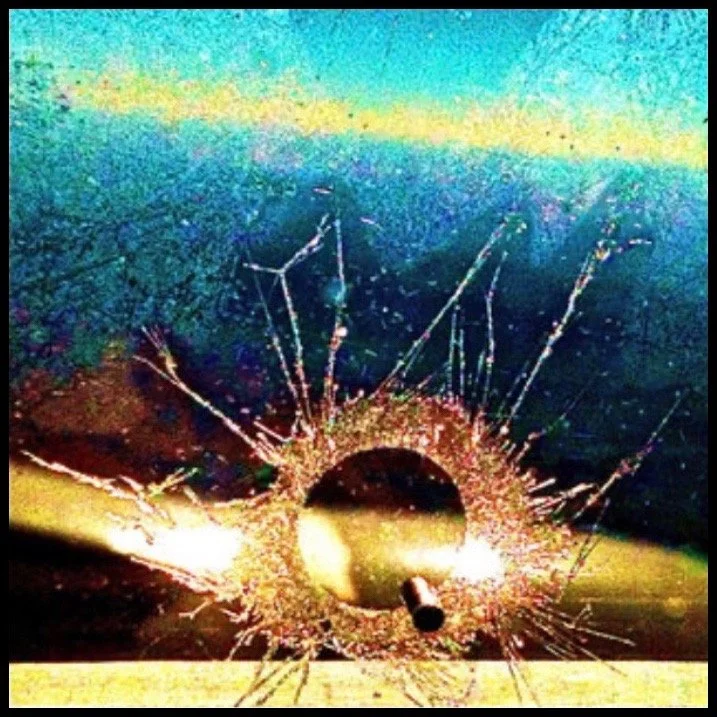

Source: Scott Bentley, used with permission

The U.S. is reeling from yet another devastating school shooting. This time 19 fourth graders and their two teachers in Uvalde, Texas, were murdered by a teenager who legally bought himself two assault rifles on his 18th birthday. And yet again, Republican lawmakers say the solution is not to ban assault weapons or raise the age for purchasing such guns or institute universal background checks, but rather to arm schoolteachers.

We resent having to engage in the exercise of explaining why schoolteachers shouldn’t carry guns. We fully understand that this idea is a cynical ploy on the part of the National Rifle Association and its GOP shills to derail actual, effective, wholly reasonable, and widely supported proposals about how to address the problem of gun violence in the U.S. Nonetheless, we explain below why arming teachers will lead to more, not less, violence.

Let’s explore the various scenarios that may occur if teachers are armed and see how the mayhem unfolds. First, widespread concealed handguns in classrooms means that unarmed students can more easily become armed students, whether they simply come across a gun in their teacher's purse (as happens with guns in the home), or they seize a gun. What if a dispute occurs between two students, or a teacher and a student? The teacher feels threatened, draws her weapon, and a student disarms her. What happens next? If the teacher did not have a gun, maybe there would be raised voices, perhaps even a physical altercation, but probably not the real possibility of homicide.

Next, let's say a mass shooting occurs at a school where teachers carry guns. How is this event going to proceed? Students and teachers hear gunshots, a teacher unholsters her weapon, makes sure it’s loaded, takes the safety off, confirms there’s one round in the chamber, and she’s ready. Not panicked, not shaking so badly from the adrenaline dump she’s just experienced, she somehow seamlessly manages her 30 panicked students. The shooting sounds are getting closer and closer. Does she engage the shooter? The NRA says, yes she does. Because the only way to stop a bad guy with a gun is having a good guy with a gun confront the perpetrator and his AR-15 with endless rounds of ammunition, a Level 4 bullet-proof vest, and backup weapons with extended clips. The teacher and her gun confront the perpetrator who has the benefit of spending months preparing for his big day. She sees him in the hallway picking off students who are running in all directions, screaming, and crying. She pops off repeated rounds. Who gets hit? Because now you have bullets traveling in two directions—more if there are several good guys with guns. Does she shoot and miss? Likely. A recent RAND study of NYPD officers found that in a gunfight (not a simulation) officers hit their targets only 18% of the time. Is a teacher with very limited training going to be a better shot than NYPD officers? Whom does she shoot and kill? The shooter or innocent students running for their lives? What if she mistakes another armed “good guy” for the shooter and shoots him? Adding guns to this situation is likely to bring about more casualties, not fewer.

One thing that some gun advocates don’t want to reckon with is that, in these dynamic situations, oftentimes the best thing to do is run and hide, not engage a shooter with your own weapon. While this fact may feel profoundly uncomfortable to some men because they see a weapon as an extension of their masculinity, this fact is no less true. The Department of Homeland Security describes what to do if you find yourself in an active shooting event. Their advice? “RUN. HIDE. FIGHT.” Notice the order: the official website of the DHS says, “FIGHT as an absolute last resort.”

Back to our schoolteacher with a gun. The police are on their way. 911 dispatch has alerted them to an active shooter situation and this is all the information the responding officers have. Let’s say, against the odds, the armed teacher shoots and hits the perpetrator. He is down. When the police arrive and see a person with a gun they do not say, “Freeze! Drop your weapon!” They neutralize anyone with a weapon. Period. And that could be our heroic teacher. There are many examples in which the police arrive at a home invasion and mistakenly shoot and kill the armed resident fending off intruders. The risk of being mistakenly shot increases if our heroic armed teacher is a person of color. In simulation studies, we find that individuals are quicker to shoot armed African Americans than armed whites (and are quicker to decide not to shoot unarmed whites compared with unarmed African Americans).

In fact, allowing or mandating the arming of schoolteachers (or, absurdly, offering bonuses for packing a pistol) will put black and brown students at greater risk. As Elie Mystal wrote, giving a teacher a gun is asking that teacher to be afraid. And due to the proliferation of racist stereotypes, who has she been told she should be afraid of? Black and brown children. Mystal writes that arming teachers “makes poor judgment a homicidal offense. And that danger will be borne by black and brown students. The students who make teachers ‘afraid’ just by their very existence.”

In a culture where white motorists lock their car doors when an African American crosses the street, white women clutch their purses in elevators, school resource officers disproportionately target children of color, and police officers and vigilantes shoot and kill unarmed black children with impunity, can we really expect that teachers will rationally appraise the behavior of students of color?

In addition to the real-life tragedies that keep accumulating, social psychology studies repeatedly show that many white Americans cannot rationally interact with people of color. White people cannot reliably interpret the emotions of African Americans—they read anger into the neutral faces of black men, whereas they accurately interpret the neutral faces of white men. The ambiguous behavior of a black individual is interpreted through a lens of hostility, while the ambiguous behavior of a white person is seen through a neutral lens. It’s no surprise then that black children are more likely to be disciplined than white children for the same infraction. When discipline issues could be handled by a trip to the principal’s office or visit with a counselor, young girls and boys of color are instead routed through the school-to-prison pipeline. Giving a gun to a stressed-out and overworked teacher is a bad idea on a good day, and it is a deadly idea given the racialized criminalization of youth of color. A tragic irony of the fact that arming schoolteachers will disproportionately hurt black and brown students is that most school shootings are committed by white men and boys.

Ultimately, there is no situation where adding guns to a scene make people safer. And politicians know this perfectly well. Many state legislatures have banned weapons from their own offices, and guns are not permitted at the U.S. Capitol. Why? Because guns are dangerous and politicians know it.

Some final points about arming our way out of gun violence. An armed guard at the Tops grocery store in Buffalo, New York, didn't prevent 10 people from being murdered by a white supremacist. An armed officer at the school in Parkland, Florida, didn't stop the murder of 17 students and staff. Armed officers at Columbine didn’t prevent 15 people from being gunned down. An armed police officer at Pulse Nightclub didn't prevent the murder of 49 club-goers. There were armed security guards in Las Vegas when 58 were shot dead and over 500 injured. Two armed military veterans (one of them a decorated sniper) at a Texas gun range couldn’t stop their own murder. When President Reagan was shot in 1981 he was literally surrounded by armed guards. An intruder who enters a school can ambush an armed guard (or schoolteacher). Or he can engage the armed guard (or schoolteacher) in a gunfight, during which many innocent children will likely die. Mass shootings happen in open carry states and even military bases, and the presence of guns has not prevented such shootings.

Finally, the idea of giving teachers guns in order to stop mass shootings trivializes the work of trained first responders. Women and men whose jobs require them to protect the public undergo extensive training to learn and practice not only the operation of weapons but also the judgment to not make the wrong call in a life-and-death situation. And while this training has been evaluated as inadequate, arming less-trained teachers is not the solution.

Neither the NRA nor the politicians in their capacious pockets actually believe that arming teachers is a reasonable or effective solution to address mass shootings. But as more and more children die, they need to say something. They need to appear to be doing something. Surely the NRA will never suggest, "How about reasonable regulations like most every country on the planet has? How about banning military-style assault weapons?" Instead, it drags red herrings across the bloody terrain of American gun violence, hoping that the furor dies down in time for its politicians to be re-elected after failing, yet again, to pass reasonable restrictions on guns.

Bios

Kristin J. Anderson is Professor of Psychology at the Center for Critical Race Studies at the University of Houston-Downtown. She is the author of Enraged, Rattled, and Wronged: Entitlement's Response to Social Progress (2021, Oxford).

Christina Hsu Accomando is Professor of Critical Race, Gender & Sexuality Studies and English at Cal Poly Humboldt. She is the author of “The Regulations of Robbers”: Legal Fictions of Slavery and Resistance (Ohio State University) and the editor of Race, Class, and Gender in the United States (Macmillan).